Hasn’t been a thing in years here. Maybe with covid restrictions on how many ppl could enter/social distancing?

McDonalds was selling their cokes for ~$1.50 for awhile and now they are back to $1.

Yeah, I don’t think I’ve ever seen it. Most big cities with legal weed have lots of places you can go.

Confirmed 9 stores for a small city population 150k. For comparison we have 3 liquor stores and 3 mcdonalds.

Never seen more than 1-2 people in any of the weed stores.

In Massachusetts my local weed store per capita is almost 3x higher, and liquor stores are about 5x higher. Do they even vice where you are?

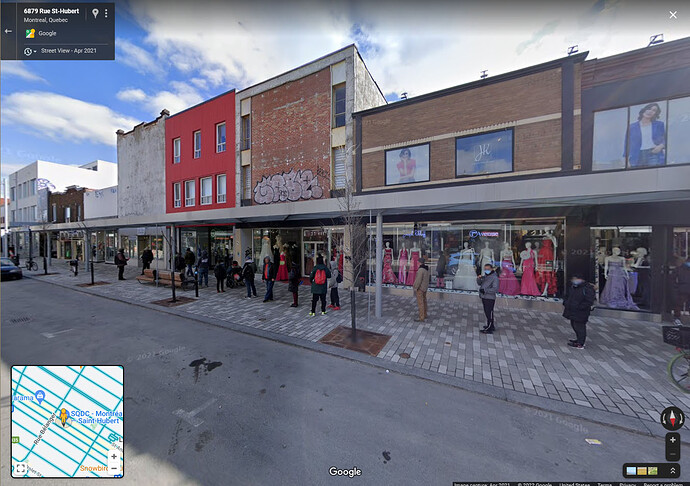

This is the line for a SQDC about a block away from where I was staying last time I was in Montreal. It was like this every day winter/spring 2021. Could have been covid restrictions. Or could just be Quebec’s famous customer service and efficiency.

I’d be pretty confident they were allowing 1-5 customers in at a time causing those issues.

3 McDonalds for 150k people? you sure?

SQDC is a different thing, it’s a government monopoly. Like the LCBO in Ontario for alcohol.

I’m talking about small privately owned shops. I think that a lot of people who opened them thought they would be getting something like a private location of a SQDC or LCBO, but those monopolies are more organized. For example the LCBO is careful not to cannibalize it’s own business by opening shops to close to each other. There are over 1,400 licensed cannabis shops in Ontario (and hundreds of licenses pending approval) but only about 700 LCBOs.

The surge in cannabis store openings was really evident. Privately owned cannabis shops have only been legal since 2018 and they’ve already opened twice as many locations as the alcohol monopoly. It’s all really weird and certainly gives the impression of an investor base overreaching the market capacity to grab hold on a lucrative new market. I am sure that some of those shops are doing fine and some people are probably realizing their big investment dreams. I’m also pretty sure that some of them are scraping by realizing that what they have set up is more like a corner store that sells cigarettes than an LCBO monopoly.

I think this is spot on.

First, LOL

AQR suffered painful losses from 2018 to 2020, with its equity market neutral strategy posting negative returns for three consecutive years.

That ain’t people being influenced by too-frequent updates to their portfolio values.

I do think there’s something interesting to the “hedge funds are clearly delaying marking to market their illiquid investments”. In one sense it seems like you’re misleading investors, which is bad. But on the other hand, don’t we advise people to ignore day-to-day fluctuations in market prices, and to only check their brokerage statements maybe once a quarter? Maybe this delayed marking-to-market is just beneficent behavior by the hedge funds - “Because we cannot trust you the investor to ignore day-to-day fluctuations in your portfolio value, we will impose that upon you by simply pretending that those fluctuations have not occurred.”

I guess it depends on the situation, but it’s hard to imagine that “hey what if we just ignore volatility” is actually going to be a net positive for investors. If that were the case, then public companies shouldn’t be subject to all the continuous disclosure requirements either.

ehh, it was me just trying to be dryly funny. I do not actually believe that hedge fund managers are intentionally delaying fair value marks in order to protect their investors from behavioral biases. (I do believe that hedge fund managers are intentionally delaying fair value marks - I know people who have written journal articles on it. But I am confident they are doing it out of self interest.)

A lot institutional investor decision making is driven off modern portfolio theory, so suppressing your volatility to make your return/risk profile attractive is certainly a good idea if you’re selling an investment product.

This issue is actually quite old, by the way. When I started in the pension industry 20 years ago, one of the first projects I worked on was an analysis of the portfolio benefits of adding real estate products to pension plans. A lot of the supposed benefits of real estate came from the fact that no one ever reassessed the market value of their holdings so the volatility in the market value of the real estate funds looked very small relative to their returns.

I will go to my grave refusing to accept beta as a way to gauge risk.

I wasn’t sure whether to post this here or in the book thread or in the Elon Musk thread where the topic originally came up, but the new Bill Gross biography–The Bond King–kind of sucks.

There are a few reasons why it kind of sucks, and I thought I’d lay them out:

- There isn’t much salacious detail about crazy behavior like you saw in Liar’s Poker or a lot of other books. Only at the very, very end do you get some stories about Bill Gross being absolutely nutso to his neighbors and his soon-to-be-ex-wife. But as far as life at Pimco, the story seems fairly clear that Gross was stubborn and introverted and didn’t care too much about pissing off other people. But there weren’t any really vivid illustrations. More like, “Person A wanted to expand into equities, and Gross told him brusquely that it was a really dumb idea.”

One example is in the description of Neel Kashkari, who joined Pimco after running TARP. In an effort to illustrate how COMPLETELY different Kashkari was from other Pimco management, the book describes this event:

When walking up to the building, a more junior person always held the door for more senior people, to allow them to walk frictionless and first into the capacious lobby. The senior people took this as expected, a function of the natural order; usually they’d pass without a nod or other acknowledgement.

Not Kashkari. One day, this lower-ranking executive recalls seeing Kashkari approach the building behind him, and the man of lower rank held the door as expected. Kashkari sped up and, upon walking in, turned his head and made eye contact.

He said, “Thanks.”

The executive froze in shock. This guy will never make it here, he thought.

I think I actually burst out laughing when I read that. Not that Kashkari held the door for other people - he just said thanks to someone.

Another sick burn:

The Wall Street Journal published a story on the showdown between Gross and El-Erian, which this book describes as follows:

The story detailed confrontations that seemed indisputably, unspinnably bad. […] That he didn’t like dissent when he’d made up his mind about an investment–arguably a rigidity that could inhibit achieving the best performance. As an example, the Journal cited a senior investment manager who thought a bond in Gross’s fund was expensive.

“Okay, buy me more of it,” Gross had reportedly replied, apparently just to be a dick.

-

Some of the reviews on Amazon characterize this as a hit piece on Gross, which is absolutely wrong - it’s evident that Gross was a primary source and had a big influence on how he’s portrayed in this book. So if you’re looking for an unauthorized true story of Gross, this isn’t really it. Even the stories that make Gross look somewhat bad have kind of a halo on them, presumably because he’s the one recounting them.

-

Related to the prior point, the author clearly spent a lot of time interviewing people. But one of the critical people who very clearly was not interviewed was co-CEO Mohamed El-Erian. The reason I know he wasn’t interviewed is that there are constant footnotes where El-Erian’s lawyer disputes facts. Here’s one of the dumbest:

In 2010, Gross was named Morningstar’s Fixed Income Manager of the Decade. Pimco/El-Erian wanted to organize a surprise party in recognition, but the problem was that Gross came in to the office so early (typically at 5am or so) that it would be hard to set the party up in advance to successfully surprise him. Here’s how the chapter describes that process:

"El-Erian had scoured Orange County for a bakery willing to deliver a cake at 4:45 A.M. It was no easy feat, but he finally found one that would do the job.*

[then, at the bottom of the page]:

*“Dr. El-Erian placed an order consistent with the bakery’s operating hours,” his lawyer says.

Other footnotes include El-Erian’s lawyer pointing out that El-Erian typically flew commercial rather than taking advantage of the company’s NetJets accout.

So it’s kind of a boring behind-the-scenes story if you’re interested in tabloid-type stuff. But it’s also very unsatisfying if you want details about trades! (I’ve got a meeting now, but will follow up with a couple of baffling descriptions.)

Putting aside the tabloid stuff, there were a few finance things that were potentially interesting, but that also made me question whether the author knew what she was talking about.

- The first one, and the most interesting one IMO, was the one that I think she talked about on the Bloomberg podcast. This was a story about how there were these Ginie Mae futures that were tied to any Ginnie Mae mortgage bond, and that allowed the holder of the future to demand delivery of the underlying bond. What makes this interesting is that (simplifying it) there were “high value” bonds and “low value” bonds. Obviously if the bondholder can choose which bond to deliver to the futures holder, the bondholder will always choose to deliver the low value bond. And so the futures are all priced on the assumption that they’ll be exchanged for the low value bond.

BUT! Pimco realized that the total supply of low value bonds wasn’t all that large. So if they could amass a total number of futures that exceeded the total number of low value bonds (and the market didn’t notice), then they’d pay the “low value” price for the futures but receive a combination of low value and high value bonds (because, again, there weren’t enough low value bonds to satisfy all of Pimco’s futures). That was a very fun finance story!

But that kind of substance was largely missing from the book. And what remained is somewhat unclear or even nonsensical. Here are two examples:

- Apparently there was a “fluke” in the bond world’s pricing systems, where bonds typically trade in $1 million blocks, but as the mortgages underlying those bonds are paid off, they shrink and can result in “odd lots” that are not very popular and therefore traded at a discount. So Pimco would buy a bunch of these round lots, and when they went to price them, the outside pricing service provided a price based only on round lots.

The example in the book:

On March 9, Pimco bought an odd lot at $64.9999 and plopped it into the system, where it was valued at $82.7459. A tidy instant gain of 27 percent, for zero work. The ETF’s “net asset vaue” (the cumulative value of everything it held) jumped by almost $0.02 per share in one day, thanks to that trade alone.

What’s annoying is that the author is completely unclear about whether this is bad! She first frames this as a fluke in bond world pricing, which Pimco takes advantage of. That would be good. But then she calls it “a game Pimco could play” and “the odd-lot trick”, suggesting this was a misleading action where Pimco was intentionally distorting the reported value of the odd lots. Then later, she says parenthetically “Years later, Pimco was in fact able to sell many of those odd lots near the reported values.”, which suggests this was a canny investing decision and that it was appropriate to value them the way they did. Finally, 130 pages later, she talks about the WSJ breaking news about an SEC probe looking into whether “Pimco had artificially boosted returns of its Bond ETF” with “the odd-lot pricing mechanism Pimco had exploited”.

Like, just take a stand on whether this was a savvy investment or fraudulent pricing.

- The most confusing one is fairly late in the book, when Gross put a $10 billion notional trade on in the equity market. In particular, a strangle that would pay off huge as long as markets didn’t move too much.

That’s whatever. What’s crazy is this description:

The dealers who bought the contracts from Pimco had to hedge themselves, which meant functionally selling the same trade as Pimco’s. Every day, dealers had to fiddle with their positions a little, to hedge themselves back to a neutral risk. [Not crazy so far.] Through this basic maintenance, the dealers themselves were acting as guardrails, pressuring in the market, keeping things within the range Pimco had delineated. It became a self-fulfilling trade.

Unless there was some external disaster–and Pimco was betting there wouldn’t be–the very structure of the trade helped make it work.

What the hell does this mean? The fact that whoever bought the strangle has to hedge makes Gross’s position a self-fulfilling trade? Maybe I am dumb, but this made absolutely no sense to me.

Overall, I don’t think this book is of interest to anyone for any reason. Not scandalous enough for the group that wants scandal, and not enough substance for the group that wants substance.

Spidercrab,

What are your favorite business books of all-time?

I’ve read most of the classics like Liars Poker, Big Short, Barbarians at the Gate and Den of Thieves, but I’m sure you have great recommendations.

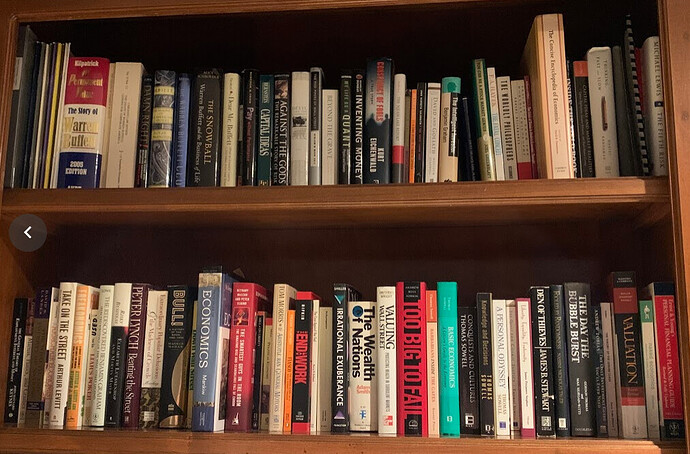

I knew I had posted about this before, but was amused to see that it was in response to you asking for book recommendations:

From that link:

This is going to get lost in the wave of STONK talk, but I’ve got several recommendations. I had to get a quick picture of my bookshelf area to remind myself what I have:

Based on those books, here’s what I’d recommend, in no particular order:

Against the Gods: Just a really good story of the history of statistics and probability, and how they made their way into financial markets.

Inventing Money: I haven’t read this in a long time, but I remember thinking very clearly that this was a better-written story of Long-Term Capital Management than “When Genius Failed”, and I couldn’t understand why “When Genius Failed” got all the hype.

Fiasco: The Inside Story of a Wall Street Trader: This is similar to Liar’s Poker, but gets more in depth regarding particular derivatives trades.

The Day the Bubble Burst: A Social History of the Wall Street Crash of 1929 : This book is pretty fascinating, and I don’t think I’ve ever seen many people writing about it. It was written in 1979 and actually covered a lot of the day-to-day activities of people tied into the 1929 crash in the immediate period leading up to the crash. I think I randomly bought this in a used bookstore.

The Worldly Philosophers: A pretty great book giving a superficial history of famous economists. I think this was the book that prompted me to go into academia. Still not sure if I should be grateful or resentful.

Some memoirs that are really good and are effectively finance books:

My Life as a Quant: A memoir by Emmanuel Derman, a physicist-turned-finance quant who spent several years at Goldman Sachs and is now a professor.

Misbehaving : Nobel prize winner Richard Thaler, who some would say is a founder of behavioral economics.

Moving slightly away from pure finance, the autobiographies of Katherine Graham (Washington Post) and Sam Walton (Walmart) are great.

I am an enormous Warren Buffett fanboy, but I’m not sure I could recommend many books about him. Definitely read the annual letters. The big biography The Snowball is a bit of a slog to get through. And many Buffett/Berkshire books are just bad (The Warren Buffett CEO and Dear Mr. Buffett are two that come to mind.)

Charlie Munger is the more interesting personality, I think - Damn Right! is worth reading. Poor Charlie’s Almanack is also very good.

I also want to be clear that I definitely don’t recommend everything on that bookshelf. (There are a bunch of books on there I haven’t even read - my introduction to Amazon in the late 1990s was me just buying an absolute assload of economics-related books as it kept prompting me with “Here are some other books you might like”.) I particular, I see at least one Gladwell book and at least one Taleb book. Don’t read those - they are infuriating.

Some books that should have been great, but weren’t:

Capital Ideas and Market Realities: Option Replication, Investor Behavior, and Stock Market Crashes: This sounds like a fantastic book, right? Focusing on portfolio insurance and how it contributed to the 1987 crash? Terrible.

Risky Business: An Insider’s Account of the Disaster at Lloyd’s of London: Again, this should be a great book, right? No

Billion Dollar Whale: The Man Who Fooled Wall Street, Hollywood, and the World: One of the greatest financial scandals in history, and this terribly superficial book is what comes out. I have no idea how this is rated 4.5 stars on Amazon.

Finally, this is a curious one: Business Adventures: Twelve Classic Tales from the World of Wall Street: This book’s claim to fame is that both Warren Buffett and Bill Gates consider it the best business book ever written. The author is a fantastic writer, but the stories just aren’t that interesting imo.

There are a couple of other books whose covers look familiar to me and I think they’re good, but I can’t quite tell what they are. I just snapped a quick picture before my wife went to bed, but maybe I’ll take a closer look tomorrow.

==========================

Since I wrote that post, I read a WeWork book that I thought was pretty good. (Billion Dollar Loser), and Lying for Money, which I thought was terribly boring. I also seem to have left off Smartest Guys in the Room, which is excellent.

Well that’s embarrassing. Thanks and sorry.

For #2:

Pimco sells a shit ton of strangles (let’s say right now it’s the 3500-4500 strikes in the SP right now)

Those are owned by prop firms that represent more risk than they normally have on. The firms now make money if they move to and through one of the strikes. Pimco makes money as long as they stay between the strikes.

As the future moves towards one of the strikes, that inventory gets larger on the books of the prop firms. This means that as they get closer to the strikes in the strangle, market makers are selling volatility, marking Pimco’s short strikes lower. They are also hedging their gamma by buying futures on the downside and selling futures on the upside, which puts more open interest in the futures market that will help keep it between the strikes of the strangles.