Graduating in '92 definitely sucked for jobs. But graduating with $10k total debt didn’t suck.

I’ve always seen Gen-X as the nothing horribly sucks, but nothing is great generation.

Graduating in '92 definitely sucked for jobs. But graduating with $10k total debt didn’t suck.

I’ve always seen Gen-X as the nothing horribly sucks, but nothing is great generation.

I made a post in April 2020 about this when I noticed that the pandemic crash had reversed this negative correlation, specifically in March 2020.

I never got around to digging any deeper to see if there were bond components that were disproportionately contributing to this, but I happened to revisit this last week to see if things had gone back to normal, and they haven’t. I still have no idea if it’s significant (or actionable in any way), but it still seems weird to me.

Are any of you dividend stock investors?

I’ve been reading up on this approach to investing–concentrating your stock portfolio in dividend aristocrats–well-established companies that have consistently paid an increasing dividend for 10, 20 years or more.

Trying to work out the pros and cons of this approach vs my current approach–plowing everything into a Vanguard Life Strategy fund.

A dividend is you being forced to liquidate a small amount of your equity whether you want to or not.

It’s not the free money event that many dividend enthusiasts seem to think it is. It’s basically neutral but it also has tax implications unless in a retirement account.

Your current approach is hard to improve on imo.

I saw this awhile ago on the internet, pretty sure from one of those libertarian financial things which is why I didn’t really get into it, biggest pros are downside risk is lower as most of those companies ain’t gonna go bankrupt if things go to shit and figuring out which ones are definitely still gonna be around say 25 years from now but even they are kinda high p/e wise for the most part and I’m not really a thing on stuff that’s unhealthy when people are slowly starting to figure out maybe we shouldn’t be doing that. of course the main one I thought about was HSY which is up pretty good since I bailed lol me.

Well I think part of the idea is that dividends are reinvested over the years, thereby deferring realized capital gains until the portfolio grows so large by retirement that you can begin to draw an income from the dividends alone sufficient to cover your life expenses.

Dividends are tax inefficient and companies that pay them have no better total return than those that don’t.

If a stock pays a 1% quarterly dividend, the stock will just drop 1% on the day it pays out.

You can pay yourself any dividend% you want for any stock. For example, ATT has paid around a 7% div for years and the stock has moved from about 35 to 25 in the last decade. It would have been about 42 if it never paid one. Disney on the other hand doesn’t offer a div. Its at 175 and would about 110 if it paid ATT’s dividends over the years.

Dividends are essentially nothing and at most are just psychologically appealing for a simple liquidation decisions.

Reinvesting dividends is nothing more than selling the percentages of shares on monday and buying the same shares on again on tuesday. It’s nothing.

Or in another way, a poker site offering 25% rakeback while charging 25% more rake at the tables.

You realize that you have to pay tax on bolded, right? Unless you’re in a tax protected account. If there was no dividend, then you don’t have to pay tax until you realize gains, which whenever you like (now, later, even never is possible). That’s what Riverman is getting at.

I assume your Vanguard fund spits out a pretty decent dividend too, so the mechanics should be the same.

Dividends count as taxable income whether they’re reinvested or not. There are some complexities (ordinary vs. qualified dividends with different tax rates) but this is independent of capital gains. Again, not really an issue for retirement accounts.

The problem with dividend enthusiasts is that they tend to focus on the number of shares they have while caring less about the value of those shares.

They love to extol the virtues of “living off the dividends” but there’s nothing particularly beneficial about this approach. It may feel better to see the same number of shares in your account after a distribution, but it ignores the value of the shares. (As @Formula72 says above, the value is always reduced by the dividend)

Similarly, during the accumulation phase whey they’re reinvesting dividends, they love to see the number of shares in their account increasing. But for the same reason, it’s a mirage.

Another risk is the lack of diversification you take on by concentrating on dividend stocks. Plus managing your own portfolio of 30-40 individual dividend stocks is a nightmare especially if you’re accounting for reinvesting.

I went down the path you’re on 10 or 15 years ago. I even read a couple of books and the arguments presented seem compelling. But I eventually decided it was all basically smoke and mirrors.

I think the research bears out that there’s no real benefit to the dividend approach. For example, Vanguard constantly publishes research papers like this one: Total-return investing: A smart response to shrinking yields (Summary)

Thanks for the responses. Don’t worry, haven’t gone down that path, just trying to understand it, and based on the responses here and my own doubts about it, I think I’ll just stick with my current set-and-forget DCA into an index fund approach, as it seems to be working fine so far.

By the way, some people do not actually believe this, they have somehow convinced themselves that dividends are free money. Sometimes they don’t understand how dividends work and are looking at the wrong day and not finding the drop. More often, a typical quarterly dividend is so small relative to the stock price that the drop can get lost in the day-to-day price fluctuations.

The way to win this argument quickly is to find a company that has recently issued a “special dividend” that is large relative to it’s stock price. For example, in early September RMR distributed a $7 dividend, about 15% of it’s value. Gee whiz, the next day the stock opened down $6.61. Pretty much undeniable.

The next phase of the argument usually starts with “Well, sure the price drops temporarily, but it always bounces back quickly since dividend-issuing companies are so strong and well-run and stable!” ![]()

Meant to post this in Poker News.

This conversation is giving me serious flashbacks to the Dogs of the Dow strategy on the motley fool, and how it took them like 5 years to admit it was nonsense. God I’m old.

Not that I don’t believe it, but the convincing argument should be an explanation of what happens on an ex-dividend date. I actually don’t know, so I’m hoping someone can explain it. Are open orders automatically adjusted? Like if I have a limit order to buy a $100 stock if it reaches $99, and they issue a 1% dividend, does my order still execute at $99? Because if the argument is just that the fundamental value of the company has decreased and the efficient market hypothesis will ensure the price reflects the new value, I’m going to be skeptical.

I’m not sure I understand which part you’re skeptical about, but limit orders are adjusted for dividends:

So if the stock is $100, you have a buy order for $99, and it goes ex dividend ($1), your buy order is reduced to $98 (per FINRA rule), and the stock price would open at roughly $99. The stock price wouldn’t go down by rule, but by basic market efficiency. I’m not a market efficiency zealot, but prices clearly go down by the amount of the dividend. It’s just sometimes difficult to see because the dividend amount is often comparable to daily price fluctuations.

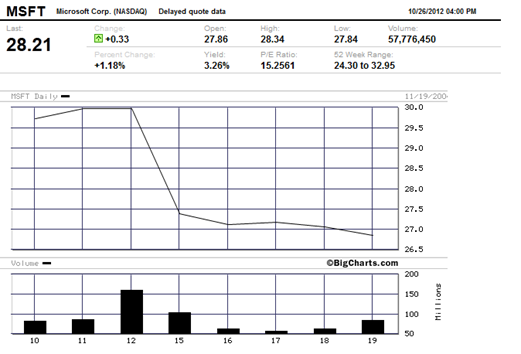

Easy example is Microsoft, which issued a special dividend of $3 in 2004, payable to holders of record as of 11/17/04. Stock went ex-dividend on 11/15/04 (to allow for clearing between trade and record date), and you saw that reflected immediately in the price change from Friday the 12th to Monday the 15th:

Edit: Probably easier to think about in terms of stock splits. You’re not skeptical about those, right? Obviously your limit orders would be adjusted for the stock split, and basic market efficiency means that the price immediately reflects the split.

If it doesn’t otherwise offer any advantages over traditional growth stock investing, I wonder if part of the appeal of dividend investing is that it gives investors a more easily trackable scorecard for how they’re doing along the way.

That is, you can gain a clear picture of the annual growing increase in dividend income you earned (or would have earned had you not reinvested it), whereas with a traditional index fund, I can see my balance growing each year, but am unsure of what this will translate into in terms of a monthly income come retirement time.

Probably the biggest advantage of a dividend heavy stock portfolio is that if you are depending on your stock portfolio to deliver income then it’s an automatic mechanism to deliver that. You can plan around receiving your dividend every quarter or month and then using it to cover living expenses.

@Riverman points out above that this is tax inefficient, which I think I agree with if what we’re saying is that a hypothetical equivalent portfolio that delivers only capital gains will be taxed less if you sell off an amount every quarter in lieu of the dividends and pay capital gains taxes on that. It can get very thorny with specific tax regimes though. In Canada the dividends on our Canadian companies are taxed less than non-Canadian companies, so there is an offsetting tax subsidy that rewards investing in Canadian corporations.

Utility stocks often pay strong dividends, partly because of their relatively, historically, predictable revenues. Electric utilities in the US are about to go through a decade-long period of investment in grid modernization, some of which will be made with regulated rates of return. Obviously the sector is in a state of change/turmoil, but I don’t think electric utilities are going anywhere anytime soon. Companies with exposure to transmission could fare well, particularly depending on what comes out of Congress in the infrastructure and reconciliation bills.