I knew I had posted about this before, but was amused to see that it was in response to you asking for book recommendations:

From that link:

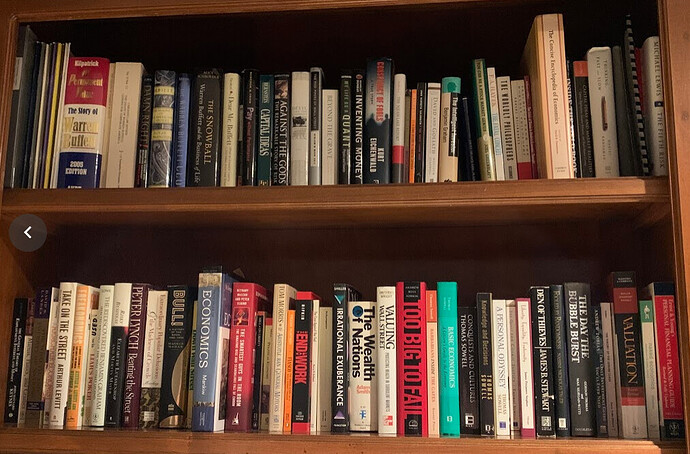

This is going to get lost in the wave of STONK talk, but I’ve got several recommendations. I had to get a quick picture of my bookshelf area to remind myself what I have:

Based on those books, here’s what I’d recommend, in no particular order:

Against the Gods: Just a really good story of the history of statistics and probability, and how they made their way into financial markets.

Inventing Money: I haven’t read this in a long time, but I remember thinking very clearly that this was a better-written story of Long-Term Capital Management than “When Genius Failed”, and I couldn’t understand why “When Genius Failed” got all the hype.

Fiasco: The Inside Story of a Wall Street Trader: This is similar to Liar’s Poker, but gets more in depth regarding particular derivatives trades.

The Day the Bubble Burst: A Social History of the Wall Street Crash of 1929 : This book is pretty fascinating, and I don’t think I’ve ever seen many people writing about it. It was written in 1979 and actually covered a lot of the day-to-day activities of people tied into the 1929 crash in the immediate period leading up to the crash. I think I randomly bought this in a used bookstore.

The Worldly Philosophers: A pretty great book giving a superficial history of famous economists. I think this was the book that prompted me to go into academia. Still not sure if I should be grateful or resentful.

Some memoirs that are really good and are effectively finance books:

My Life as a Quant: A memoir by Emmanuel Derman, a physicist-turned-finance quant who spent several years at Goldman Sachs and is now a professor.

Misbehaving : Nobel prize winner Richard Thaler, who some would say is a founder of behavioral economics.

Moving slightly away from pure finance, the autobiographies of Katherine Graham (Washington Post) and Sam Walton (Walmart) are great.

I am an enormous Warren Buffett fanboy, but I’m not sure I could recommend many books about him. Definitely read the annual letters. The big biography The Snowball is a bit of a slog to get through. And many Buffett/Berkshire books are just bad (The Warren Buffett CEO and Dear Mr. Buffett are two that come to mind.)

Charlie Munger is the more interesting personality, I think - Damn Right! is worth reading. Poor Charlie’s Almanack is also very good.

I also want to be clear that I definitely don’t recommend everything on that bookshelf. (There are a bunch of books on there I haven’t even read - my introduction to Amazon in the late 1990s was me just buying an absolute assload of economics-related books as it kept prompting me with “Here are some other books you might like”.) I particular, I see at least one Gladwell book and at least one Taleb book. Don’t read those - they are infuriating.

Some books that should have been great, but weren’t:

Capital Ideas and Market Realities: Option Replication, Investor Behavior, and Stock Market Crashes: This sounds like a fantastic book, right? Focusing on portfolio insurance and how it contributed to the 1987 crash? Terrible.

Risky Business: An Insider’s Account of the Disaster at Lloyd’s of London: Again, this should be a great book, right? No

Billion Dollar Whale: The Man Who Fooled Wall Street, Hollywood, and the World: One of the greatest financial scandals in history, and this terribly superficial book is what comes out. I have no idea how this is rated 4.5 stars on Amazon.

Finally, this is a curious one: Business Adventures: Twelve Classic Tales from the World of Wall Street: This book’s claim to fame is that both Warren Buffett and Bill Gates consider it the best business book ever written. The author is a fantastic writer, but the stories just aren’t that interesting imo.

There are a couple of other books whose covers look familiar to me and I think they’re good, but I can’t quite tell what they are. I just snapped a quick picture before my wife went to bed, but maybe I’ll take a closer look tomorrow.

==========================

Since I wrote that post, I read a WeWork book that I thought was pretty good. (Billion Dollar Loser), and Lying for Money, which I thought was terribly boring. I also seem to have left off Smartest Guys in the Room, which is excellent.