The database isn’t a journal. They didn’t withdraw a paper. They deleted a bunch of partial sequences from a database. Two different databases, actually.

https://twitter.com/stuartjdneil/status/1407695935283531778

https://twitter.com/stuartjdneil/status/1407712642010169352

Notice the honesty here instead of trying to change what was said.

Do you think his tweets are in conflict with his statement in the Telegraph? They aren’t.

https://twitter.com/stuartjdneil/status/1407597242496716803

Regarding the “ouch” tweet:

https://twitter.com/RVirologist/status/1407693613102940177?s=20

Fun and wildly irresponsible!

Right, ignore all the highly respected virologists who seem to think this is a big deal and, uh, link to an anonymous satirical twitter account?

They absolutely are, and it’s clearly after he got the same new information you’re foolishly handwaving away based on… I’m not sure really.

How in the world are his tweets and his statement in the Telegraph inconsistent? Bloom’s paper doesn’t inform the lab vs nature debate, Bloom never said it did and Neil didn’t either.

And what’s this new information that I’m handwaving away?

Holy shit, that’s not new information. He knew that the mutations and samples were published from reading Bloom’s paper. Bloom said that’s how he figured out the sequences were deleted in the database! Like, it’s a page of Bloom’s paper.

I assume one answer to this is that the paper only considered genome regions related to genes coding for virulence-related proteins:

To realize the detection of pivotal SARS-CoV-2 virulence genes, we focused on the virulence region (genome bp 21563–29674; NC_045512.2) encoding S (1273 amino acids; AA), ORF3a (275 AA), E (75 AA), M (222 AA), ORF6 (61 AA), ORF7a (121 AA), ORF8 (121 AA), N (419 AA), and ORF10 (38 AA) proteins. We also considered the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRP) region in ORF1ab (Figure 1).

Bloom says he was able to reconstruct entire partial genomes:

I was able to use the data in the files to reconstruct partial viral sequences (from start of spike to end of ORF10) for 13 of these samples. (6/n)

This might include additional point mutations (e.g. in non-coding areas) which would assist with phylogenetic reconstruction. Even “there aren’t any other mutations” is still important information to have before you can put the complete sequence in the database.

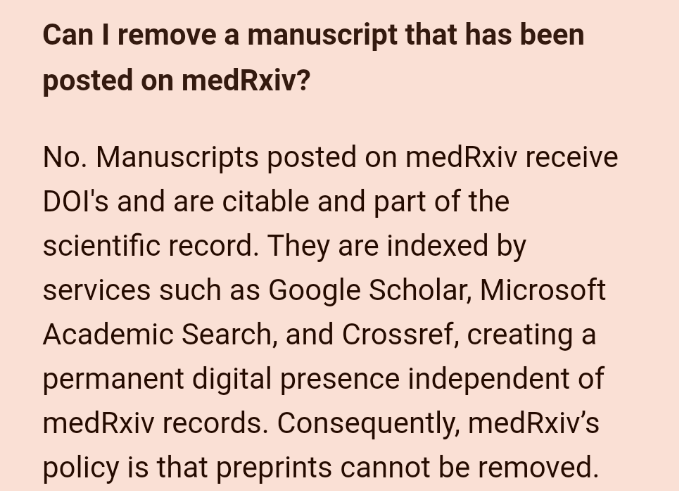

So basically the case against the Chinese government here is that the data was removed from the database which is what everyone uses to do phylogenetic studies. The fact that the point mutation data was included in a paper doesn’t really absolve them of charges of a coverup, since it is not possible to delete preprints once they are uploaded to medRxiv:

The guy who originally posted that the information was available in a paper conceded that this matters:

https://twitter.com/stgoldst/status/1407724668912504832

If they retract the paper, it probably gives the preprint more attention than it would otherwise get.

Bloom updated the thread with an addendum thanks to an anonymous Twitter user:

https://twitter.com/jbloom_lab/status/1407542297659514886

It’s difficult to come up with a legitimate reason for this coordinated deletion. If there’s some problem with the sequencing, they should also have retracted the paper.

I don’t think this helps a lot with origin theories because what it seems to demonstrate is that China thinks it’s possible an investigation would lead back to the WVI, which is to say that they’re not sure where the virus came from, which we already knew. Since their trips out to Yunnan to collect viruses seem absurdly unsafe, as we discussed earlier, this doesn’t even imply that viruses similar to SARS-CoV-2 were under study in Wuhan. An employee there could be patient zero even if that is not the case.

There’s some speculation in one of those threads that the publication of the paper is what cued the censors to realize that the sequences were publicly available and take them down. It’s also possible (and softly suggested in the Bloom paper) that posting the preprint and/or the sequences themselves was done to front-run the imposition of the censorship scheme.

Bloom seems to think his work backs up a progenitor proposed by these guys, which they claim could have been circulating as early as October or even September? That would seem to blow up everybody’s origin theory! Man, this will be hilarious if it turns out China has been torpedoing evidence that shows COVID started months before the Wuhan outbreak.

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-021-92388-5

In silico comparison of SARS-CoV-2 spike protein-ACE2 binding affinities across species and implications for virus origin

The devastating impact of the COVID-19 pandemic caused by SARS–coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) has raised important questions about its origins and the mechanism of its transfer to humans. A further question was whether companion or commercial animals could act as SARS-CoV-2 vectors, with early data suggesting susceptibility is species specific. To better understand SARS-CoV-2 species susceptibility, we [did a bunch of science stuff zikzak doesn’t understand]

…

These findings show that the earliest known SARS-CoV-2 isolates were surprisingly well adapted to bind strongly to human ACE2, helping explain its efficient human to human respiratory transmission.

…

Conspicuously, we found that the binding of the SARS-CoV-2 S protein was higher for human ACE2 than any other species we tested, with the ACE2 binding energy order, from highest to lowest, being human > pangolin > dog > monkey > hamster > ferret > cat > tiger > bat > civet > horse > cow > snake > mouse. At its extremes, this ranking accords with experimental observations that humans are highly permissive to SARS-CoV-2 infection whereas mice on the other hand are not susceptible.Potential significance of high S protein binding to human ACE2

During the early pandemic, S protein mutations were rare, especially in the RBD region interacting with ACE2. Notably, three mutation sites, V367F, G476S, and V483A were identified within the RBD of some SARS-CoV-2 isolates but only G476S was in the binding interface and its incidence and geographic spread was very small38. This minimal S protein RBD mutation during the early pandemic supports the view that the SARS-CoV-2 S protein was already optimally adapted for human ACE2 binding. This finding was surprising as a zoonotic virus typically exhibits the highest affinity initially for its original host species, with lower initial affinity to receptors of new host species until it adapts. As the virus adapts to its new host, mutations are acquired that increase the binding affinity for the new host receptor. Since our binding calculations were based on SARS-CoV-2 samples isolated in China from December 2019, at the very onset of the outbreak, the extremely high affinity of S protein for human ACE2 was unexpected. This high affinity was confirmed in July 2020 by Alexander et al.39 who similarly found that the SARS-CoV-2 S protein RBD is optimal for binding to human ACE2 compared to other species. They also commented upon this as a remarkable finding that likely underlies the high transmissibility of SAR-Cov-2 virus among humans. Our results are also consistent with a study that found SARS-CoV-2 RBD bound with much higher affinity to hACE2 through additional hydrogen bonds and hydrophobic interactions when compared to binding of the SARS virus RBD to hACE234.

…Implications for the original SARS-CoV-2 animal source

Bats have been suggested as the original host species of SARS-CoV-2 infections in humans. Bat RaTG13 has the highest sequence similarity to SARS-CoV-2 with 96% whole-genome identity, but RaTG13 possesses neither the furin cleavage site nor the pangolin-CoV-like RBD seen in SARS-CoV-2 (Fig. 1, lower panel). Although bats carry many coronaviruses, no evidence of an immediate relative of SARS-CoV-2 in bat populations has been found so far. As highlighted by our data, the binding affinity of SARS-CoV-2 S protein for bat ACE2 is considerably lower than for human ACE2 and other species. Notably, RaTG13 S protein was shown not to bind to human ACE255. Hence even if SARS-CoV-2 did originally arise from a bat precursor virus, which remains unproven, it must have spent considerable time in an intermediate animal host to allow it to adapt its S protein sufficiently to then be able to bind human ACE2. There are currently no explanations for how or where such a transition could have occurred to generate a SARS-CoV-2 spike protein optimised for human ACE2. Evidence of direct human infection by bat coronaviruses is rare, with transmission typically involving an intermediate host. For example, SARS CoV was found to be transmitted from bats to civet cats in which it first adapted before becoming able to infect humans. Hence SARS S protein had to acquire specific mutations to enable each species transition to occur, first to increase its affinity for civet ACE2 and then to increase its affinity for human ACE2. To date, a virus directly related to SARS-CoV-2 has not been identified in bats or any other non-human species, leaving its origins unclear.

I found the title of the following section and the language used awfully surprising for something published in Nature.

Does high human ACE2 binding affinity represent a recent gain-of-function mutation?

…

Given the seriousness of the ongoing SARS-CoV-2 pandemic, it is imperative that all efforts be made to identify the original source of the virus. It remains to be addressed whether SARS-CoV-2 is completely natural and was transmitted to humans by an intermediate animal vector or whether it might have arisen from a recombination event that occurred in a laboratory handling coronaviruses, inadvertently or intentionally, with the new virus being accidentally released into the local human population. Resolving these questions is of key importance so we can use such information to help prevent any similar outbreak in the future. In summary, our study suggests that from the beginning of this pandemic the SARS-CoV-2 S protein already had very high, optimal binding to hACE2. There is minimal early evidence of selection pressure to further optimise binding, in contrast to what has been seen with other zoonotic viruses at the time of their entry into the human population.

Why?

He didn’t realize that Nature hated Chinese people.

Because it’s implicitly pointing a finger at not just a lab leak possibility, but lab engineered one. I don’t think I’ve seen something in such a major publication go that far before.

It’s in the WHO report too. So I’m left confused.

Yeah like there was no reason for them to even mention gain of function experiments, they could just report the data. The insertion of the heading suggests they think this is at least a reasonable possibility. It’s a bit surprising they’re willing to speculate on a politically-fraught interpretation of the data in the middle of a scientific paper.

I’ve been following Nature and Science and they’ve both been openly talking about these kinds of possibilities since the beginning and I assume the core journals in the field have also been doing this. Science just published that letter co-signed by Bloom like a week or two ago!

Speaking of, Science has a tidy synopsis of the recent Bloom stuff:

All of this seems pretty bad for the Deliberately Engineered theory afaict. You’d have to buy that this gain-of-function-engineered super-strain was introduced into a major city and kicked around for months(!) before the wet market super-spreader event.