If you’re going to argue against points I didn’t make and assign me positions I didn’t claim I’ll just see myself out since there’s not really much for me to do in the imaginary discussion you’re having.

You are misreading this poll. The question (posed in early 2019) asked “is pipeline capacity a crisis”. This is a pretty stupid question in my opinion. That doesn’t require the respondent to make any choice or acknowledge any of the compromises necessary to build a pipeline. If you asked “do you support increasing pipeline capacity even if it means violating indigenous people’s land rights and contributed to worsening climate change for your children” you would get a different answer that is probably more relevant to the question of the protests in 2020.

No your question would be stupid and leading because the conclusions don’t draw from the premise.

I didn’t misread anything. They were asking if the lack of capacity was a problem which means people want MORE pipelines.

Of course it was a poll of its time.

Yes that’s the point. If you ask people if they would like X to be better, it biases them to say “yes”. If you ask them if they want more X but with the horrible side effects Y, they are biased toward saying “no”.

The most objective thing we actually have to go on is the results of the last federal election, which more or less showed that people are about evenly split between short term gains vs. long term pains when it comes to things like pipelines.

If you asked would you prefer more pipelines or your children being murdered the results would be predetermined.

Building pipelines does not have anything to do with violating indigenous rights and in many cases it is better for climate change than alternatives.

You are embedding your conclusion in the question. It’s a good thing you are not a pollster.

The main reason I disagree with these protests is the company explicitly did not violate indigenous rights. They got consent.

In summary, from their perspective,

-The hereditary chiefs of the Wet’Suwet’en don’t agree with the elected chiefs. I don’t know for sure why but it could be a caste/family disagreement which are common among First Nations because democracy does not always easily map onto their existing social structure which are often based on membership in defined social or family units.

-while I’m sure they dislike this pipeline, they are more interested in using pipelines as leverage to address larger indigenous issues because it’s the only thing the media seem to care about.

-there is an immense amount of anger and disgust with how First Nations are being treated and how Trudeau has lied to them promising over and over to address their concerns and doing basically nothing.

-this justified anger is leading other First Nations to take drastic action trying to get attention for their cause by shutting down rail lines in support for the Wet’Suwet’en. They choose rail lines because they don’t have pipelines nearby and often can’t afford to engage in “protest tourism” and travel west.

This is a half truth at best. Claiming they got consent is intentionally evading the matter at hand. From whom did they get consent? Did they have the right to grant consent? Is their consent enough? These are meaty public policy matters and on matters of social justice the argument “we followed the law so it’s right” is transparently weak. You are not really engaging at all on what the protests are about.

I understand where you’re coming from and these are useful lines of thought, but a truly thoughtful analysis of the situation includes some understanding of what the objections to the pipeline are. You are just blaring the pro-pipeline message over and over again with a general theme that the protestors are just too stupid to understand why you’re right. It’s not a very compelling case.

It dawned on my people don’t really understand the process. I am going to make a few posts on the process for those interested.

First Nations consultation works basically the same way across Canada. There are two types.

For small projects it’s works like this (small

can mean hundreds of km pipelines as long as they don’t traverse provincial or international boundaries).

Consultation is legally required when a project traverses Crown land. On private land there is no consultation.

First Nations receive funding from the government to establish consultation groups. They hire people on the reserve to deal with the process. The amount of funding is not enough in areas with heavy oil and gas activity.

The company sends a notification package to the First Nation consultation group. It contains a map and some information on the project.

They are legally required to wait a preset amount of time for a response (often 21 days). If no response they move on with their project. If they get a response there is no clock. The process takes as long as it needs.

The First Nation normally says they want to visit the project area. They send out a group of people, often elders and young people, learning traditional knowledge, to walk the site and look for concerns. The company pays them for this (often about $5,000/day).

After the visit the First Nation sends the company one of two letters, non-objection meaning they have no concerns or objection meaning they have one or more concerns.

If non-objection the company forwards the letter to the regulator, along with a detailed record of all correspondence.

If objection, the company must resolve the concern. Common concerns are the presence of traditional plants or wildlife habitat, prayer sites etc. Common mitigations are moving the project or allowing harvesting. First Nations are not allowed to object on general principal to all projects. They must show a direct impact of that project.

Once the issue is resolved to the satisfaction of the First Nation they write a non objection letter.

For large projects, like costallink, it works basically the same except the government takes a larger role and the company must engage the entire community with open houses. They are not allowed to only deal with the consultation group. Also private land triggers the process as well.

For Transmountain, there were hundreds of such open houses.

This is my issue with these protests. The company would have gotten consent from the elected arm of the First Nation and held one or more open houses with the community.

I’ll write a post later on the problems with the process. There are many. It sucks for First Nations and companies for a number of reasons.

Timelines are useful to understand.

For small projects consultation takes 3-6 months. For large projects it takes 1-4 years.

That breakdown is meaningful and useful content Clovis. I agree generally with your four potential motivations for first nations ppl. I disagree with you about nearly everything else.

This kinda means the whole process is bs, no? Unless I’m misunderstanding and we’re saying that the land doesn’t actually belong to the people the canadians genocided.

This is one of those things that sounds good in principal but makes no sense in action.

No doubt there was a wholesale stealing of land from First Nations and many have legitimate moral (if not legal) claims for huge swaths of Canada.

I have no idea what that means in execution. We can’t reasonably give back BC to First Nations.

I’m going to say that Clovis has destroyed everyone else in this thread. It’s basically fact after fact after fact vs. bad oil companies, power to the people, and misapplied minority rights

This conversation is going all over the place and well beyond the context of protesting coastallink.

Let me add a bit more background.

First, I promised some insight into why consultation is a broken process

For First Nations they often don’t have capacity to manage all the requests for consultation they get. They don’t have staff who understand oil and gas or opportunity to train them. They are also not allowed to generally object but must do so project by project. There is no real mechanism to address cumulative effects. As in, maybe this pipeline is ok and that one is ok but together they trigger an effect (e.g., loss of wildlife habitat).

It’s doesn’t work for companies because they often know little about First Nation structure, customs or history. They also get frustrated by the opacity of the process.

Perhaps the biggest issue is consultation has devolved into a de facto tax. Legally consultation can’t be about money or business arrangement between First Nations and companies. But because they often lack capacity to engage in the process the company often pays very high fees as a de fact subsidy to the reserve. Government has tacitly avoided funding First Nations like they should because this shadow tax exists. They should create a real tax that passes through to First Nations or better a profit sharing model for projects that traverse their lands.

It also might be useful to understand what “traditional territory” actually means.

First Nations today have legal ownership of their reserve. These are often pretty small.

Their traditional territory is the lands they historically operated in before European contact. They are often huge.

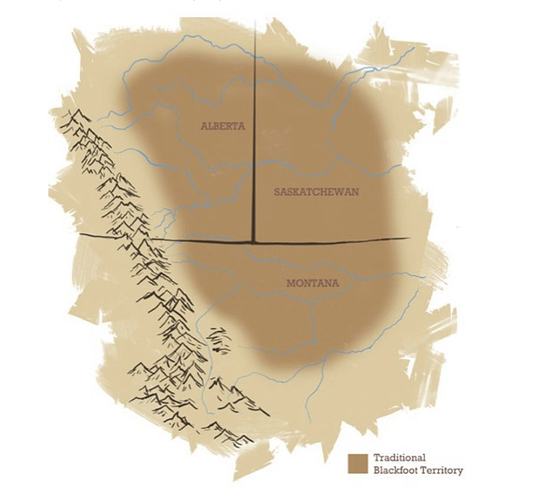

For example, the Blackfoot today are on 4 small reserves but their traditional territory covered all of Northern Montana, Alberta south of Edmonton and parts of Saskatchewan.

See this map

So when you say First Nations should have approval authority, or even more significant, granted their land back this is what it means. Lands currently occupied by millions of people and containing the financial engine of significant portions of Canada.

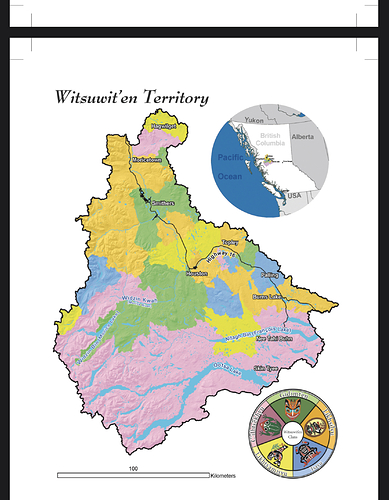

Here is the Wet’Suwet’en traditional territory.

Last post

I have sat in hundreds of meetings and dozens of hearings with First Nations and pipeline companies.

Here are my observations,

-

First Nations often don’t understand how oil and gas facilities work. This is not surprising or different than any other group of lay people. This leads to some of the same misunderstandings that many people have. Oil and gas companies have done a very poor job of helping First Nations better understand their business.

-

the most common concern is “spills” which actually means rupture or leak from the pipe. This does happen but is very rare. It also poses little to no risk to people. It can be a significant environmental stressor although we are pretty good at cleaning up. When there is a leak the pipeline company must pay all costs to clean it up.

-

the next most common concern is loss of habitat. This concern is justified as loss of habitat has real effect on the ecosystem. This is commonly addressed by routing in already disturbed lands or doing full reclamation.

-

I have NEVER heard a First Nation frame their concern about a pipeline project because it would allow more oil and gas extraction and therefore contribute to climate change.

-

in my experience, it is very uncommon for First Nations to actually have a real problem with a pipeline. However, Canada has set up a regulatory system whereby pipelines are one of the very rare things that legally FORCES a discussion between them and government. It is their only chance for an audience. They understandably leverage it to address their broader concerns which often have nothing to do with the actual project in question.

This is all true but has nothing to do with pipelines (see my post immediately above).

If the question is what should the government of Canada do about First Nations? The answer is way way more. They should spend huge amounts of money improving conditions on reserves and providing education and training. They should revamp the consulting process to make it more meaningful. They should have mandatory First Nations members of the house and senate. They should scrap the Indian Act and restructure INAC. They should explore a version of reparations.

But again, none of these things has anything to do with pipelines.

I think this is partially true. Clovis is knowledgeable about the matter and has valuable insights. But he’s also too far on the “inside” of one side of the debate. So when other people say “well climate change is serious and so maybe we shouldn’t be approving controversial pipelines” or “well the system for engaging native Canadians on these matters is horrendously broken and lies on a foundation of illegitimacy” he doesn’t acknowledge that stuff at all. He is dismissing those matters as irrelevant because stupid protestors don’t know the intricacies of how pipelines get approved. It’s a pretty classic forest for the trees situation.