I remember reading an ancient history book where it turned out that bundling up a whole bunch of property debt turned out to be not very safe at all.

I think they were bundling up a whole bunch of high risk property debt and then re-selling it as low risk instruments? (I honestly know very little about the specifics but think what I wrote here is generally true.)

Yeah, but the risk was only seen in hindsight.

Yeah, although some of the people involved certainly knew the game they were playing. I’m suggesting bundling all property debt is probably low risk. Bundling specifically high risk property debt probably remains high risk.

But if you chop up all those high risk mortgages and pile a bunch of pieces together, there’s no way you can lose money

Pension plans and insurers like mortgages. We have to match long term liabilities with long term assets. If I back my pensions with treasuries the yields are too low. We use a basket of treasuries and corporate bonds and private lending and mortgages to match the pension payments we need to pay.

That’s what the finance bros thought, but what we discovered in '08 is that it’s possible for broad changes to affect wide swaths of the mortgage market. That’s why we had to nationalize Fannie and Freddie.

I think we discovered that a giant pile of high risk loans remains high risk even when bundled together.

I mean, all things being equal, you’d probably rather own 1% of 100 mortgages than 1 mortgage. But when 50 of the 100 mortgages are to people with no job and no money, the benefit of diversification evaporates.

I mean, it sort of depends on the EV of the mortgages (and the assumption that you’re obligated to own at least one mortgage for the purposes of the exercise). If the mortgages are +EV, then you dramatically lower your variance by owning a little bit of a lot of them, which in this cases is good. But if they’re -EV, you’d rather just have 1 to maximize your variance hand hopefully bink one of the ones that comes out on top rather than locking in the loss.

Obviously there is still risk but what they did in 2008 that made it so disastrous was a pure scam that is not being replicated today.

They said if you took the risky B-/C tranches of each RMBS from different regions of the US and packaged them together then somehow they weren’t risky at all and got a AAA rating because never before had all regions of the US suffered any meaningful decline all at the same time.

If you just held real AAA tranches of RMBS (as opposed to mixed together shit relabeled as AAA) you would have come out fine even factoring in the insane underwriting standards for mortgages at the time.

Not saying there aren’t different scams going on now but shouldn’t assume they are just running the same scam all over again. Regulators are okay at fixing things after the fact, their shortcoming is predicting the next scam.

Yeah, I think it’s important to understand that there really is some genuine alchemy available in packaging and slicing these loans, and to be able to distinguish the valuable stuff from the stuff that gets you in trouble.

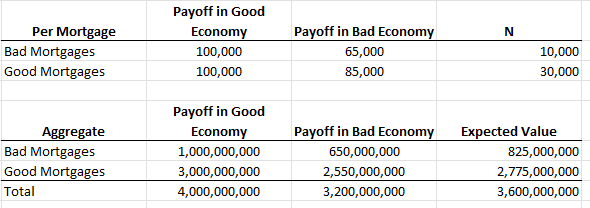

Just to put some numbers on it for those who are curious. Say you’ve got a pool of loans, $100,000 each. You have two groups of borrowers–30,000 good ones and 10,000 bad ones–and you can roughly categorize them based on credit score. In good economic times, all borrowers will repay the full loan value. In bad economic times, “good” borrowers (in aggregate) will be able to repay 85% of the loan value, while “bad” borrowers will be able to repay only 65% of the loan value. Assuming good and bad economic times are equally likely, you get this aggregated distribution:

So if you buy the aggregated pool, you have an expected value of $3.6 million, but it’s risky - the payoff is $4 million in good times, but only $3.2 million in bad times. That’s moderately risky - if you purchase at $3.6 million, you stand to either gain 11% or lose 11%.

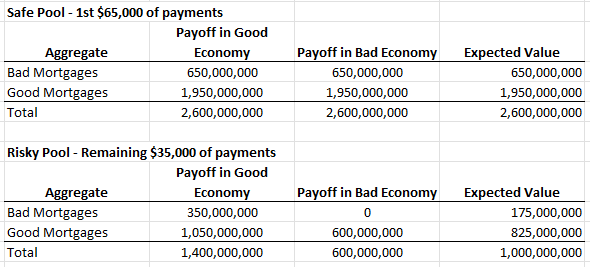

The genuine alchemy is to create two separate pools:

- a senior pool that’s entitled to the first $65,000 of value recovered from any loan

- a risky pool that’s entitled to any remaining value recovered from loans after the first $65,000

The distribution of those look like this:

The senior group really is a risk free asset with an expected value of $2.6 million, as long as you’re confident in the assumption that you’ll recover at least 65% of each loan. If you buy at $2.6 million, you’re certain to not lose money.

The expected value of the combined pools has to be the same as it was before they were separated, so that leaves $1 million of expected value for the risky pool. But that junior group is much riskier than the original pool - the two possible outcomes are 40% more or 40% less than the expected value.

The two problems here are:

-

Bad assumptions, of which there are multiple. You can summarize these as being either "underestimating the extent of possible losses (maybe you only recover 40% of bad loans in bad states, rather than 65%) or "underestimating the breadth of possible losses (maybe you thought in a diversified pool only 20% of mortgages would default, but actually 50% did because the correlations are much higher than you predicted).

-

Carrying this on to extremes, where you say, “Wow that risky pool looks way to risky for my blood. But we already know what to do with risky assets - we’ll just chop those up into even more junior and senior securities!”. And if you create those sliced-then-reconfigured securities with little margin for error, you create a very fragile set of securities that can evaporate with the slightest unexpected development.

Add to this the fact that firms are purchasing these riskier-than-realized assets with leverage, so the purchasing firms not only own risky assets but are themselves very risky, and you’ve got systemic banking system fragility.

Not good!

This is correct but the securitization of mortgages wasn’t just applying the law of large numbers by pooling mortgages and averaging the outcomes. They were pooling mortgages and then dividing them into tranches, where Tranche A got all their payments first, then Tranche B got their payments if there was still money left over after Tranche A got 100 cents on the dollar, then Tranche C got their payments if A and B got paid, etc. etc. They basically undid the benefit of pooling and averaging by concentrating the default risk in Tranche C, and then badly underestimating the probability that of defaults. Tranche C was rated as low credit risk and used that way in bank balance sheets, and then kaboom.

Tranche C seems like an extremely risky and shitty investment. Surely the wizards buying Tranche C could see this too?

Standard securitization structure still being used to underpin multiple asset classes today. People invest for perceived higher yield. In 2007 the idea all regional housing prices could correlate and decline simultaneously was unthinkable

I guess we’ve done a full 180. Now it’s unthinkable that anyone would think that.

For mortgages, there are some very complicated tax rules about what the interests in the securitization can look like. Basically all the interests have to look like debt, except for the most junior interests, which get bad tax treatment.

I’m sure we have other risks we are blind to today.

I understand this well. Rich people use debt as a wealth-building strategy. Poor people fall into all kinds of debt and can’t get out of it. Wage increases keep pace with inflation and make it easier for some to pay off their debt, but not others. I’ve seen instances of both firsthand, and I imagine most others here have as well. I’ve been on the wrong side of inflation (stagnant income while being priced out of the skyrocketing real estate market) and the right side (watching my equity holdings soar into the stratosphere). The only thing that really saved me was making a massive lifestyle change–it’s not as though the power of inflation finally began working its magic.

So my point is that it’s not simply a matter of debt in times of inflation is good for all, including the poor, provided they blow all their money and refrain from saving because their wages will rise over time. It’s good for some and bad for others, but when it’s bad it can be brutal, and catching up can be near impossible.

Yes, very well summarized.