There are lots of excellent business books that I can recommend, but one of them is absolutely Smartest Guys in the Room, which covered the Enron story. (Read the book, but don’t see the movie - it sucked.)

The Blockbuster deal is really something, and it’s revealing about the mindset of the people running Enron. I’m doing this from memory, so I’ll probably get the details slightly wrong, but this is the general idea:

The people running Enron, particularly Jeff Skilling and Andy Fastow, were convinced that business ideas were the things that created value. The people who had the ideas were the ones who should be rewarded, and the people who carried out the ideas were just ditch diggers - interchangeable workerbees.

A corollary to this belief is that, if you believe that business ideas were the true value creators, then profits should be recognized when those ideas are created, not when the ditch diggers implement them. So in this case, Enron and Blockbuster team up to conduct a pilot program for Video on Demand. They called this project Project Braveheart. This was a complete nothingburger that Blockbuster never really even officially recognized. But the Enron guys were convinced that this was going to be an enormously valuable technology. (And looking at Netflix, Disney+, et al. now, they were kind of right.)

So in their minds, they had already created the enormously valuable idea, which means that they should be able to recognize the obvious profit of that idea, even though no such profit had happened yet. So they ended up packaging the future cash flows to that project and selling them to CIBC (and very possibly guaranteeing that CIBC wouldn’t lose money, but I’m not positive about that). So that allowed them to recognize about $100 million of profit on a business venture that completely didn’t exist.

Now, if CIBC literally paid them $100 million for this bogus venture, then I guess it’s reasonable to record that as profit. It’s not Enron’s fault that CIBC made a dumbass purchase. But I believe Enron also created a special purpose entity that included the Project Braveheart asset, and marked that Project Braveheart asset to market despite the fact that obviously there was no market for it.

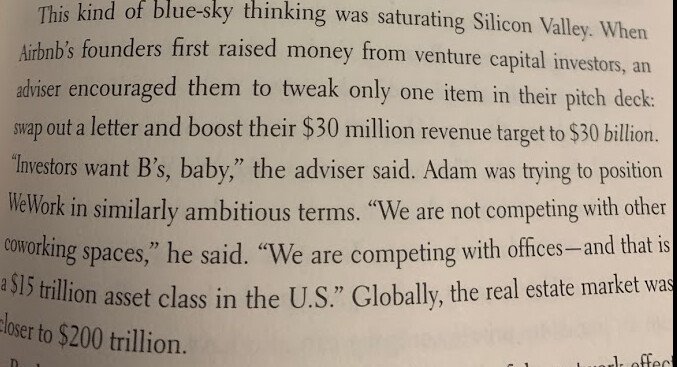

Also fun is the Nigerian barge transaction, which is just completely straightforward fraud. That book is so good that I’m probably going to have to reread it. At least they were using some fairly sophisticated accounting shenanigans to jack up their valuations. These recent businesses like WeWork and AirBNB are just like “let’s write some big, completely unsupported projections in our powerpoint deck”.

I mean, look at this nonsense: