Also invest accordingly, the plunge will happen on Monday, December 21st. It’s a lock.

Only 17% for me, SAD

What kind of finance bro are you?

He’s a lawyer, so alcohol is the drug of choice.

… Props to them for sitting on their hands to this point. That’s insane.

Tesla is worth 11 Hondas right now. I’d love to figure out some way to bet against it but I’m a fish so it will be worth 20 Hondas in 2021.

What you’re experiencing is why I stopped shorting stuff after losing like 15% of my net worth to Netflix after bumping my net worth 20% by betting against it. (I was short right before Quickster and House of Cards hadn’t come out yet… I thought they were fucked honestly. LOL me.)

Yeah this was younger dumber boredsocial at work. Modern boredsocial is a huge nit whose only financial products are berkshire hathaway stock and some vanguard retirement date stuff.

People stay religious all their lives. I would’ve shorted the hell out of some weird long haired dude with a few magic tricks and some pablum about loving thy neighbour but here we are 2000 years later and the bubble still hasn’t popped. Yes, in this analogy elon musk is jesus, but that’s how some of these tesla peeps talk about him.

Lololol I know many people don’t like Musk but the tsla bears are for sure worse.

I hate Musk but I laugh every time TSLA moons after having followed that thread for a couple of years back at nazi central.

Ya financial pain for tooth is one of the more just things ever.

You know he doesn’t have any actual money on the line, right?

Can someone explain this to me like I’m 5-years-old?

Let’s say I think a particular stock is going to go down in the future. I could either short the stock or buy puts. Why would someone choose one strategy over the other?

Tesla puts are mega expensive.

Why?

Also, I’m interested in the general case and not Tesla specifically. I’ll edit my post.

Shorting has a longer time window. Puts expire at a certain time - so you need to feel comfortable that the stonk will not only go down, but do it in a timely manner.

Of course shorts have their own downside in that you can lose infinite money if the stonk keeps going up (short squeeze) - but the most you can ever make is 100% if it goes to zero.

As a practical matter, how often do people short stock for more than a year or two.

Also, can you just buy a put that expires after a really long time?

It’s a complicated question (and even more complicated when you consider that some stocks are hard to short - you have to pay for the privilege and risk having those shorts called away at times you don’t want them to be). Picture the distribution of potential returns for the stock in question. Shorting the stock or buying a put, even though they’re both negative directional bets, are targeting and exposed to different components of the distribution.

First, the basics:

-

If you short a stock, there’s no initial outlay and you simply earn the negative of the stock return. If the stock goes up, you lose money. If the stock goes down, you make money. The payoff line is just a constant slope.

-

If you buy a put, you spending money now, but you’re limiting your downside. If the stock goes up, you don’t lose any more money. If the stock goes down, you make money but only if it goes down beyond the strike price of the put. So the payoff line is flat above the strike price (the payoff is $0), and increases linearly as the stock goes below the strike price. Now, you can choose the strike price of the put you want to purchase, so you control the shape of the payoff function.

Which is better? It’s a trick question. There’s no free lunch in the equity/options market, so neither one is better. (Actually, shorting is probably marginally better because the transactions costs are larger for options.) Again, it depends on what you think the distribution of future returns looks like. For someone just starting to think about this, I think it makes sense to just map out the potential outcomes.

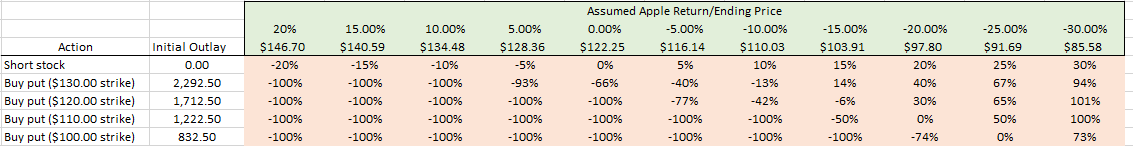

Suppose you think Apple is overpriced, and you’re trying to decide how to take advantage of that. It’s currently trading at $122.25 per share and you’re interested in betting against 100 shares of Apple. Let’s say you’re considering 5 different strategies:

-

Short 100 shares at $122.25. There’s no current outlay, but you face unlimited downside risk. Your net return will just be the negative of Apple’s return over the holding period.

-

Buy puts on 100 shares expiring in January 2022 with a strike of $130. That will cost you $2,292.50 and will have a payoff of 0 if Apple stock closes above $130 at expiration. It will have a payoff of 100*($130-close) if Apple stock closes below $130 at expiration. And your net return will be your payoff divided by $2,292.50 - 1.

-

Buy puts on 100 shares with a strike of $120 for $1,712.50, otherwise same terms as the $130 options.

-

Buy puts on 100 shares with a strike of $110 for $1,222.50, otherwise same terms as the $130 options.

-

Buy puts on 100 shares with a strike of $100 for $832.50, otherwise same terms as the $130 options.

How do these various strategies compare to one another? It depends on the performance of Apple stock over that period. Suppose you believe that the return could be anywhere from -30% to 20%. Here are the returns to each strategy:

You should be able to recreate this chart on your own. (If you can’t recreate these payoffs/returns, that would be a good indication that you shouldn’t be shorting stock or buying puts.) But there are some important patterns:

-

Shorting a stock gives you a very linear return. You’re exposed to losses if the stock goes up, and those losses increase as the stock goes up higher, but you also profit from even very small negative returns.

-

Buying puts makes you indifferent to the magnitude of stock increases. If the stock goes up by 10% or by 20% or by 30%, it doesn’t matter - you lose 100% of your initial purchase price regardless. But you don’t lose more money if the stock goes up by 20% than you do if the stock goes up by 10%. Your loss is limited to your initial investment.

-

There’s a cost to that limited loss for buying puts - you don’t profit until the stock price really goes down. For example, suppose you buy the $130 put and Apple stock goes down by 10%. You would think that’s great news. But you still lose - the put cost you $2,292.50 and your payoff is only ($130-$110.03)*100, so your net return is -13%.

-

You can lower your upfront investment when buying puts by buying lower-strike puts (e.g., buying $100 puts rather than $130 puts will cost $832.50 rather than $2,292.50). But the likelihood of those lower-strike puts finishing in the money is smaller, so there’s a greater chance that you lose the entire purchase price. Even if Apple stock declines by 20%, you still end up losing 74% of your investment.

I think the best way to really understand the differing economic characteristics are just to model out the different payouts.

But the short story is: don’t short stocks or buy puts. This is still true: