Exactly, boomers are mainly to blame for this.

Now if minimum wage increased 8% a year then maybe houses should too.

Exactly, boomers are mainly to blame for this.

Now if minimum wage increased 8% a year then maybe houses should too.

5% per year, plus not paying rent tho.

Well in a lot of cases they’re paying a mortgage for a lot of the appreciation period, so instead of renting property they are just renting some money.

I should have said this yesterday - also not meaningful to equate housing appreciation to your own salary growth. While I doubt that most people see 8% wage growth through the last 15 years, it would nonetheless be irrelevant. Comparing my salary to what I was making in 2009 is also apples to oranges. 15 years ago I was just starting out and the young guy in my department, now I am mid-career and in my peak earning years. The right comparison is how much I would be making if I was just starting out now vs. in 2009. Since I have the paperwork on that I can tell you it works out to an annualized increase of around 2.5% which I suspect is typical.

Conversely, my apartment should be worth less then it did 15 years ago because of depreciation - we were much further away from replacing the boiler and elevator etc. Hell last year we spent 200k repairing the facade and the brick is still in worse shape then in 2009. But I can tell you that prices here have gone up much more then 2.5% a year!

No disagreement. I’m simply observing that many people liken the appreciation in real estate in certain areas to like investing in Google or Bitcoin or something. Whereas the reality is if you take a big number, compound it at 6-9% over 15+ years, you end up with a very large number.

If you’re not rich by now, you never will be. At least not through your equity holdings.

https://twitter.com/dollarsanddata/status/1797606911212171714

Hmm seems less surprising than Nick wants us to think. First, he’s looking at the first 10 years out of 40 (i.e., a quarter of the contributions) and saying they account for over half of their value. So they are punching a little above twice their weight. Good.

But I doubt many people have steady savings over a 40 year period. Most consistent savers probably start modest, and increase their savings as their earnings increase (hopefully faster than their expenses) over the course of their career.

Anyway, not sure what point I’m trying to make.

His last line is stupid enough that it detracts from the whole post, but it is good to remember to save and invest early, even if money is tight.

Yeah and go even further seems like approximately zero percent of people would save the same each year in an absolute dollars sense like he saying for 40 years.

The more relevant thing would be seeing what it looks like for someone to save a fixed percent of salary with salary growth representative of the median career salary progression path.

While I am often a critic of encouraging people to save for retirement, I do get a little chuckle at a system that only works if you commit to it when you are young and broke. Very amusing.

I do this kind of analysis all the time for work running my employer’s retirement plans. If I take a simple model:

Employee works 25 to 65

Salary grows 5% per year in their 20s, 4% in their 30s, 3% in their 40s, and 2% thereafter

Assume the contribute 10% of pay per year

Assume a 7% investment return

then at age 65 we find

38% of their retirement balance is from their first 10 years of savings

29% from years 11 to 20

20% from years 21 to 30

13% from last 10 years

It’s all academic though, hardly anyone saves a level % of pay over their whole career.

There is a great book by a Canadian retirement expert that sets out the “rule of 30”, if you dedicate 30% of income to housing + children + retirement savings then you end up just fine (in Canada, under a reasonable set of assumptions). This is way more consistent with the lived experiences of typical households that need to save for retirement beyond government old age programs.

Im sorry, where can you today find places to live for only 30%, let alone the rest of it?

I’m not clear on what your question is. There are 15 million Canadian households across a wide range of household incomes and cost of living situations.

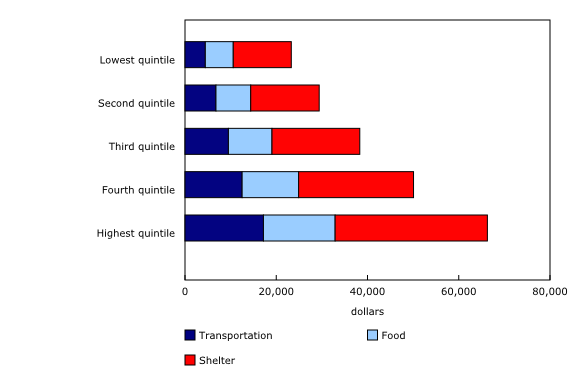

Here’s a chart that might explain a little bit of the context:

As household income climbs, the percentage spent on housing climbs. The retirement savings problem is largely a problem of the higher earning households because the government social security systems provide more proportional support for the lower earning households.

As far as how people actually behave (even if not optimal) about what year of their life contributions generally end up accounting for the highest percent of retirement savings balance? I know there a lot of variability

ETA - of folks who are “successful” in retiring although doesn’t necessarily need to be optimal

It’s typical for people to save a lot more in a rush toward retirement because they realize they’e behind. However, a lot of those people are behind because they allocated a ton of their free cash flow earlier in their career on housing, i.e. a leveraged investment in their home. In a market with rising housing prices, they’re probably still farther ahead than they would be had they saved in a retirement account.

Assuming a fixed nominal savings amount per year over a 40 year career is really dumb.

Hypotheticals can be useful to make a point, but this one doesn’t really make a point. Every insight needs to be combined with a “so what” conclusion to have any value. The implied conclusion here is that people should save more earlier in their careers, but for employees faciing serious debt burdens or that have an opportunity to get into the housing market a decision to save more earlier for retirement is not obviously better for them in the long run.

You said 30% should be spent on housing, children, and retirement.

My (and a lot of other americans) housing alone is way more than 30% If we follow that rule outline we have nothing extra to go towards children or savings.