I’ve got the 2X ratio at age 52.

For retiring at 65, 25x annual expenses and a 4% annual withdrawal rate is a good rule of thumb. You can count pensions and SS as 25x whatever the starting amount is, but watch out for inflation adjusted vs. not. For earlier retirement, you can use a lower withdrawal rate, and keep more money in stocks. For a 40-year-old, I would use a 3% withdrawal rate, and mostly ignore SS, so a 4:3 ratio, not really close to the other numbers mentioned.

You can run numbers with pensions, SS, college costs, etc., with the cFIRESim calculator: https://cfiresim.com . If you’re at like 95% probability of not running out of money, go for it. There’s another tool that shows the likelihood of being dead or broke, based on much simpler numbers. It turns out you’re a lot more likely to be dead than broke.

This is what I figured most of the answers would look like. So, I thought that I was crazy wanting 2X, but it turns out, that’s actually lower than what a lot of people would feel good with.

This is good analysis but I would definitely encourage you to go a little deeper. The retirement savings problem is complicated and there’s lots of good insights if you model out your personal household situation in more detail.

One thing that becomes evident really quick if you actually try to build a complete executable plan is that the entire tax and SS system is framed around the idea of working up to, and then retiring, at or around 65. This comes with a whole bunch of subsidies for that behavior and a whole bunch of penalties for trying to buck that system. Some earlier retirement “penalties” to model out:

-

It is important to consider where exactly you would invest your theoretical assets at age 45 and how that would be taxed vs. age 65. If you work and save to age 65, you accumulate a ton of tax exempt investments at retirement that will continue to enjoy tax deferral in retirement. But even if you are sitting on $X at age 45 you will likely have to invest it mostly in taxable accounts and that tax drag makes it much harder to meet after tax income needs over the long term.

-

Similarly, if you work to age 65 you will accumulate a very powerful social security benefit, guaranteed for life, indexed to inflation. If you retire at 45 you need to come up with the money to replace that source of income and there’s a bunch of headwinds to that - you will need to pay tax on investment earnings on those assets and you’ll have to either pay for the longevity insurance or build in a buffer in the savings.

When you start accounting for these refinements they can make a big difference, depending on personal circumstances that drive things like household tax rates.

I would add health care. For me, that’s roughly $30k per year, tax free. I haven’t looked into exactly where the Obamacare subsidies kick in but a) if you have enough money to retire early you’re probably going to have significant dividend and interest income and b) those plans suck and have huge deductibles and copays.

Indeed. I live in Canada and look at everything through a Canadian lens so the health care gap isn’t as significant (but it is present).

Yes, the Obamacare subsidy cliff was real. For now, it’s removed, but the law needs to be changed permanently. There are a few ways to keep your income low. First, don’t spend as much – the less you spend, the less you need to draw down your retirement accounts. Second, use the Roth IRA ladder technique to move money from pre-tax accounts to Roth accounts. Third, take withdrawals from Roth accounts, which do not count towards the Obamacare MAGI.

As for taxes on non-retirement accounts, there are a couple of techniques. First, use tax-efficient funds, such as index funds, rather than actively managed funds. Second, the long-term capital gains tax on income up to 80k (MFJ) is 0%, and above that, 15%. So if you can live off of less than 80k/year in capital gains, you won’t pay any income taxes. And third, of course, use all of the tax-deferred and tax-free vehicles available. These can even be used in semi-retirement to manipulate AGI (examples: HSA and deductible IRA), if you have some earned income.

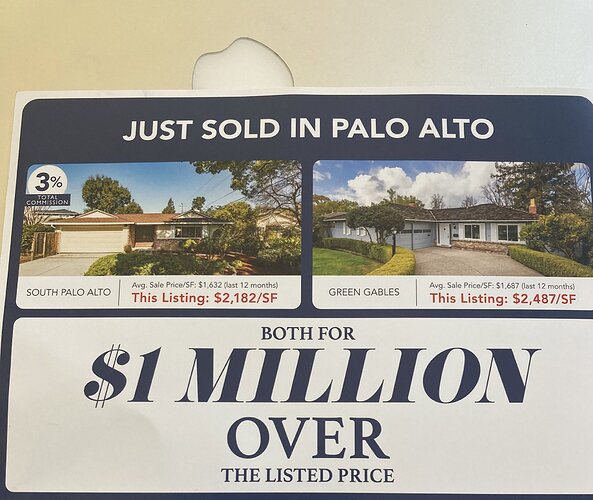

I thought Chicago housing prices were insane. What I don’t get about Palo Alto housing is that it doesn’t even come with the benefits of being in a major city. Like you don’t get world class dining or entertainment without driving an hour into San Francisco (assuming some traffic)

My wife used to work for a company based in SF and her boss lived in or around Palo Alto in a basic house like the one in those pictures. He bought it 10 years back I bet it’s worth 5x what he paid, sick life.

I don’t get living there either Zim, can’t all the tech bros work remote?

My wife got into a 17 month program to get her masters and principal license. It’s going to cost around $17k. She applied for FAFSA but it’s currently showing she is eligible for $0 assistance. Hard to tell if it isn’t updated yet or if that’s true. I assumed she would be eligible for some sort of assistance even though our income is decently high but nowhere near extreme.

I always think of Vancouver as the height of absurdity when it comes to housing prices…this is about three times that.

Are we sure that people are actually buying these to live in and not just parking money?

Yeah but you’d have to live near French people

shudder

What’s that?

In early retirement, with a low income (living off of taxable investments or a mega-backdoor Roth*), you convert money from pre-tax accounts (401k, etc.) to Roth IRA accounts. You have to pay tax on the conversion amount, but because your tax rate is lower than when you were working, the tax is lower than it would be if you contributed directly to a Roth while working, or converted all at once. Here’s one link: Build a Roth IRA Conversion Ladder to Minimize Taxes in Early Retirement - Retire by 40

After 5 years, you can withdraw Roth contributions without tax or penalty. So those funds that were locked up in a 401k are now available for living expenses. You convert a year’s worth of living expenses each year, including after you start to withdraw from the Roth, until all pre-tax money is in the Roth account. Ideally, this is complete before required minimum withdrawals (RMDs) start (age 72 now).

One big caveat is if you have both pre-tax and after-tax accounts, you have to convert in equal proportion from both sources. So if you have 100k in a pre-tax rollover IRA, and 25k in a non-deductible IRA, you would like to just convert the 25k and pay no taxes, but instead, you have to take 20k from the rollover and 5k from the non-deductible. One way to mitigate this is to keep pre-tax money in employer-sponsored plans, which are exempt from this so-called pro-rata rule for Roth conversions.

* A strategy using after-tax 401k contributions, which are quickly converted to Roth, if allowed by the employer plan. This allows up to $64500 total contributions for 2021, including pre-tax, employer match, catchup, and after-tax.

Thanks for the explanation. This was something that I thought was kind of intuitive, but I didn’t know that it had a name that everyone called it (i.e. “Roth ladder”).

How does this work, exactly?

Let’s say I contribute, in 2021,2022,2023,2024,and 2025. In 2026, I can withdraw the 2021 money, but it’s mixed in with everything else. Do you have to set up separate Roths for each year?

You just have to keep track of your yearly contributions, and in 2026, you can withdraw the amount of any contributions from 2021 or earlier. My Vanguard employer account has the mega backdoor contributions separated out by year, which is nice. If you don’t have that, just save your annual summaries at least for that account.