I am a total chess noob. I know the rules and have played many times but know zero strategy. What’s my best app/tool to learn?

Diamond membership chess.com. Tutorials, tactics trainers, video lessons, Silman articles and of course playing lots and lots of games.

Just got pitted against a Russian called White-Pride on chess.com. Reported him (after beating him).

Find an old copy of Chessmaster 9000 and watch the Josh Waitzkin lectures.

John Bartholemew’s videos on youtube are great - particularly the “Chess Fundamentals” and “Climbing the Rating Ladder” videos. Eric Rosen and GothamChess are also good for instructional content. but I find Bartholomew to be the best at teaching out of the bunch.

Chessable.com has a bunch of free courses on basically any opening you want.

@clovis8 same question was just asked on LC thread, my response is here. As long as you feel like you’re generally losing or winning games because someone hangs a piece, tactics training is the answer. After that I’d probably recommend watching agadmator’s videos - although not the Morphy saga he’s doing at the moment, I think it’s more instructive watching modern masters. I personally find being shown the correct answers over and over again with explanation a better way of learning than trying to read theory. His videos are a nice accompaniment to a morning coffee.

Just for you Clovis, I’m going to write up some crucial positional ideas for intermediates. I am a strong intermediate myself (1700-1800 5+0 chess com). These are all generally interrelated.

1. Central Control

The center is the squares e4, d4, e5, d5 and to a lesser extent all the squares which surround those four. Central control basically gives you a lot more freedom to move your pieces. It’s difficult to move your pieces from one side of the board to another if you have no space in the center, for example if you are black and e6 and d6 are not available, you are very cramped.

2. Space

Space is a more general idea of control of territory via pawns; central control is a special case of this. If you advance your pawns, space behind them will appear for your pieces to move. This exists in tension with the idea of pawns being overextended; you must be able to defend your pawns lest they become a weakness. Which brings me to:

3. Pawn Weaknesses

“Pawns are the soul of chess” - Philidor, 1749

“The pawn, as Philidor put it, is the soul of chess, and we can add that in the ending it is nine-tenths of the body as well” - Reuben Fine, 1941

I could have put this at #1 as it’s the most common way (other than them hanging a piece) of gaining advantage against bad players. Pawn weaknesses come in three basic flavours: backward, doubled, and isolated (also overextended, as discussed last point, however whether an extended pawn is a strength or a weakness is often unclear even in master games). Having multiple of these deficiencies compounds the weakness. Having more pawn islands than your opponent is a weakness akin to isolation. Weak pawns are liable to be targeted. Either they will end up captured, or you will be forced into a passive position to defend them. Passivity is as bad at chess as it is at poker. Frequently pawn weaknesses arise as a tradeoff against accomplishing other goals. That’s fine, but don’t create them needlessly. Experience is the teacher of when pawn weaknesses are OK; watching master games is an exceptional way to learn about this.

4. Good and Bad Pieces

Good pieces are pieces which have a lot of potential moves and exert control over useful squares; bad pieces control no useful territory. A good rule of thumb if you can’t come up with a plan in a position is to find your worst piece and improve it. Activating pieces is a very common reason for pawn sacrifices in master games; very frequently changes in the pawn structure can make good pieces bad and vice versa, keep a lookout for such ideas.

5. Color complexes

This is heavily linked up with good and bad pieces. Your bishops are special pieces that only operate on one square color. Your pawns should complement your bishops, so if you have a dark squared bishop, it will be much happier if your pawns are on light squares. This is especially true if your opponent has a light squared bishop and you don’t. In that case, your pawns on light squares serve to limit your light-square disadvantage. This advice applies to the middlegame only. In endgames, it’s often better to place your pawns on the opposite color to an opponent bishop to avoid them becoming targets. The relevant question is whether you want your pawns to be doing work for you, or whether they are simply assets you’re trying to preserve.

I disagree that playing doesn’t help much. Avoiding blunders is largely a “vision” thing, which you get better at over time. Seeing stuff in puzzles really not the same as seeing them in games, because your mindset going in is so different.

This is not to say that puzzles and other forms of study aren’t important, they definitely are, but they should really be complemented with playing games IMHO.

I’m really enjoying agadmator’s channel and improved a lot (granted - i am a total novice) by simply watching his explanations and legit trying to find plays

My dad taught me when I was 6 and idk if it makes a difference playing from such an early age, but I definitely got better (100 rating points maybe) when I started watching agadmator. I agree just playing does not help, because you just repeat the same mistakes over and over.

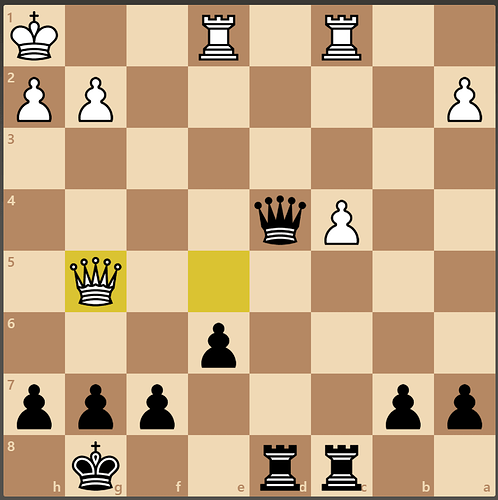

I guess the only general advice I can give is that I think most players pay way too much attention to their own plans rather than thinking about what their opponent is trying to do. Here’s an example from a game I played today, let’s all laugh at ChrisV:

I have just played Qd4, centralising the queen to try to press my advantage, and my (100 rating points weaker) opponent just played Qe5 to g5. I’m three pawns up and he hadn’t played well up to this point, so I was like LOL ok buddy, some doomed attempt to try to mate me, whatever, nice one. I played Rxc4, he played Rxc4, I played Qxc4 and was most distressed when he played Qxd8 checkmate.

This blunder arose because I was too dismissive of my opponent. Qg5 in fact indirectly defends the pawn on c4. If he had been a better player I would have spent more time trying to figure out why he played the apparently pointless Qg5 and seen this. A lot of my blunders happen this way, and I think players in general don’t give nearly enough thought to opponent plans.

It’s an idiom…

pit (someone or something) against (someone or something else)

To set someone or something into direct conflict, opposition, or competition against someone or something else.

While this is true, I think asking why your opponent played a move helps a ton with this. In the blunder above, part of the problem is also that my rook on d8 is defended twice, so my automatic danger signals about loose pieces did not kick in. If a piece of mine is attacked and only defended once, my attention will naturally be drawn to it as a potential target.

Chess is a highly situational game. Questions like “should I develop my knights first or my bishops” only have the answer “it depends on the position” which isn’t very helpful.

Beginners are given various rules of thumb that, being beginners, they apply universally.

One thing I think helped my game was experimenting more with accepting/inviting doubled pawns in compensation for other things eg piece activity or gaining the bishop pair in a non-closed position or opening a file against his king.

Before then I think my biggest leak was wasting too many tempi playing a3/a6 or h3/h6 to prevent a pin that I didn’t really need to worry about.

But learning tactics first (they’re fun) so you can recognise them in play, basic mating patterns with K+Q v K, K+R v K and the first half a dozen moves or so of a small number of openings are good places to start.

Right, I agree with this. Something I’ve started doing more after watching a lot of agadmator’s annotated master games is accepting some disadvantage to trade my way out of another one. This is intimately tied up with being able to evaluate positions well. It’s important to be able to tell when a position is just terrible with no counterplay, because once you make that determination, you can start thinking about fairly radical steps to avoid it. Accepting a pawn weakness, or pawn sacrifice, or even an exchange sacrifice is not a problem if it avoids a passive, hopeless position.

Progress is often too slow to notice and rating isn’t a foolproof method for detecting it.

If you wan’t something to study, endgames are good. Also the practices here might help Practice chess positions • lichess.org

I need to study endgames, they are definitely the weakest part of my game. They’re so boring though.

The Chessable.com site linked to above has some very good free tutorials on all aspects of the game.

has some really good end game tutorials including the dreaded rook and pawn endings, that taught me things I didn’t know about b, c, d, e and f pawns in some endings.

I usually charge $500 for this course on Udemy, but I’ll offer volume I itt for free. Endgames in three easy steps with smrk4:

- Blunder a won and/or drawn KP vs K ending for the 500th time because the concept of opposition makes your head sad

- Take a shame shower

- Click New Game

I think endgames are quite interesting. Mainly because every move can be the difference between win or draw, or between draw and loss. I think openings are very boring, because if you know your theory and your opponent doesn’t, you might end up with a tiny advantage.